Are the financial pillars strong enough?

In the last couple of months there have been a series of concerns about the financial pillars of our modern society. The core of our financial system has long been prudently managed by banks with a long-term vision of where they should be. Are the financial pillars strong enough?

For most in the community, banks undertake three different fundamental functions; they:

-

- guard our savings

- lend money

- provide financial intermediation.

In the secondary level, since last century, they have also provided:

-

- asset management services

- risk management advice

- custody services.

For their privileged position, banks:

-

- have a high level of regulatory supervision

- a strong duty of disclosure

- requirement to say no when a transaction is not in the client’s interest or that of the bank.

What we have seen since the 1960’s is banks having to accept that they need to be leaders in financial technology, reduce costs and increase profits. Banks and bankers have also learned that steady as she goes is not exactly what shareholders are looking for, and in turn, what management get rewarded for. Most of us know if you want a behavior to be repeated by your staff, to reward them for it. Many bankers add multiples of their base salary through financial engineering, first on behalf of their clients and later, on behalf of the institution that they are engaged to manage.

The time for innovation in banking

After the global financial crisis (GFC)(2007-08) regulators called on banks to have more capital and funds available via standby facilities including liquid securities. Put simply, if you need more capital to do the same business then your return on capital falls. All other things being equal, the sister to this is if your return on capital falls so does your share price.

Innovative bankers then needed to find ways to increase their returns, which generally means more risk, and find other instruments which they could hold as capital for regulatory purposes but did not reduce as much the return to existing shareholders.

During the Covid years soft dollars were effectively provided to banks so that they could lend and/or not foreclose on existing loans so that the economy continued as best it could during the shutdowns. As the world moves away from special requirements for Covid-19 banks are needing to re-finance these positions in a world of increasing interest rates and where most of their potential financiers face the same issues. Increasing interest rates also increase the riskiness of the facilities that granted to their clients.[1]

One lesson that has been learned from the GFC is the banks do not hold significant amounts of securitization bonds.

Only the largest banks are required to mark to market their long-term bond portfolio which they may need to call upon (sell) if they have a liquidity issue. Long dated bonds decreased in market value as interest rates rise – cover bank needs to sell them; they face a capital loss. In the event of a run central banks will only lend against the mark to market value of the portfolio.[2]

Conservative banking?

There it is reasonable expectation that increase conservatism within banks resulting in less lending and any increase in the cost of lending will see the seeds for a global recession.[3] The recent increase in interest rates back towards their long-term historic norm is of itself not sufficient reason to suggest that there should be a recession. The real issue lies in the action of bankers as they try to protect their own institution and share price. A good sign is that people are continuing to spend, so providing stimulus to the economy.

Why Not Australia

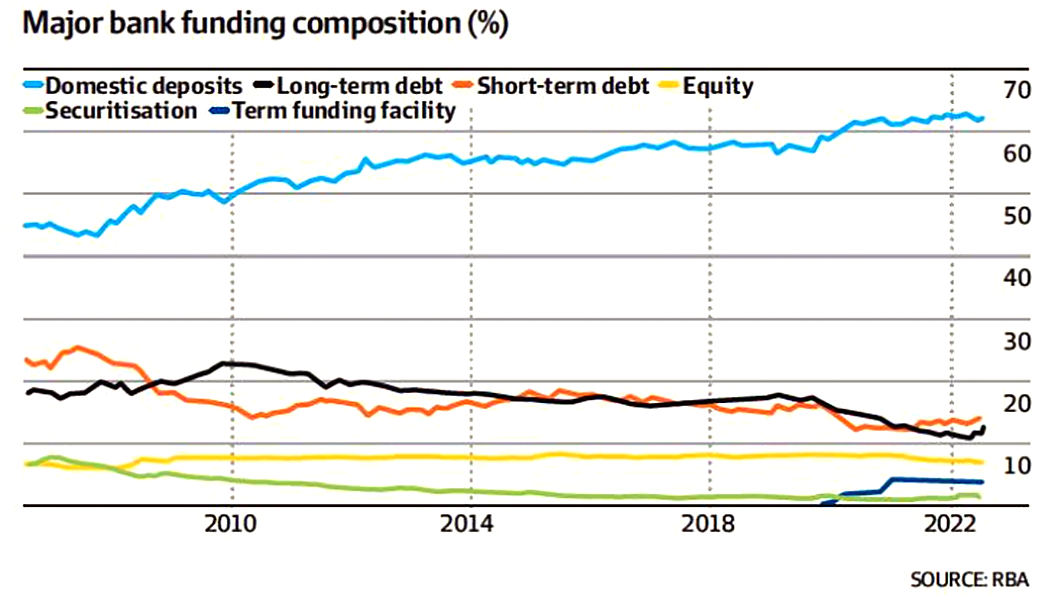

In the last decades the essence of banking in many OECD countries has changed. In the case of Australia, in the last 15 years, bank funding now has over 70% from domestic deposits where 15 years ago it was about 50%. In essence, there is less hot money in the economy. Today banks have more equity as a percentage of the total funds. Over the last year whilst dealing with increased interest rates they have already been running down their short-term facility granted by the RBA. Australia’s major banks co not hold significant amounts of paper issued as part of securitization with reduced volatility coming from this.

Back to fundamentalism

Australia’s banks are seeing a return to fundamentalism from a banker’s perspective. During the last decade, since the end of the GFC, the banks have looked at innovative ways to fund themselves including the issuance of hybrid securities. In the case of the Australian banks, they have been available to be converted into equity when required. The security should not be confused with those issued by other banks and in the case of Credit Suisse were converted and were found to be valueless after conversion.

The four pillar banks in Australia, the five major banks in Canada and the three lead banks in Singapore are examples of banks which are highly supervised and are always required to disclose information as to their solvency including that the banks stress test (wargame) their solvency and the scenario of contagion with other banks.

2023 is a challenging year particularly as major international banks review their credit exposure limits to each other and their ability to get credit insurance. We can expect to see the rise of more non-bank lenders in the middle market and insurers in international markets. We have warned the clients of Projects RH that the effective cost of debt in their models needs to be reconsidered not just as simply a margin over a benchmark but rather the price they will have to pay to get the credit they need, and this may well include: increased fees, the cost of lending from nonbanks and premiums for insurance.

This will dampen the economy and reduce inflationary pressure, but it should not stop good projects.

By Paul Raftery – CEO, Projects RH, based in Sydney.

If you have any questions, please call +61 451 523 547.

[1] “How Deep is the rot in America’s banking industry?”, The Economist, 16th March, 2023.

[2] “What’s wrong with the banks: Rising interest rates have left banks exposed. Time to fix the system—again” The Economist, 16th March 2023.

[3] Casselman, B.; “Banking crisis and volatile markets rekindle US recession fear”, 3/20/2023. The New York Times